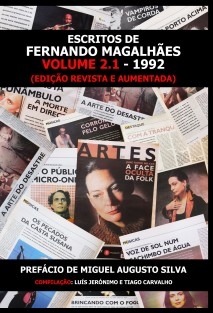

capa

A YEAR

IN THE COUNTRY

CATHODE

RAY AND CELLULOID HINTERLANDS

Stephen

Prince

contracapa

The

rural dreamscapes, reimagined mythical folklore and shadowed undergrowth of

film and television

A Year

In The Country: Cathode Ray And Celluloid Hinterlands undertakes in-depth

studies of films, television programmes and documentaries and wanders amongst

depictions of rural areas where normality, reality and conventions fall away

and the landscape becomes deeply imbued with hidden, layered and at times

dreamlike stories, taking in modern-day reinterpretations of traditional myth

and folklore and work that has become semi-obscured from view through being

unifficialyly available or otherwise having become partly hidden away.

It

explores film and documentary hinterlands including, amongst others, the

embracing of the ‘old ways’ in The Wicker Man; John Boorman’s creation of an

otherworldly Arthurian dreamscape in Excalibur; the alternate retelling of folk

legend in Robin and Marian; the unreally vivid seeming snapshots of folk

rituals in Oss Oss Wee Oss; the slipstream explorations of The Creeping Garden

and stories from the ‘haunted borderlands’ in Gone to Earth and The Wild Heart.

The book

also investigates the hauntological spectral and ‘wyrd’ undergrowth of

television, including, alongside other programmes, the unearthing of mystical

buried powers in Raven; the utopian meeting of starships, pedlars and morris

dancers in Stargazy on Zummerdown; teatime Cold War intrigues amongst bucolic

isolation in Codename Icarus; Frankenstein-like meddling away from the mainland

in The Nightmare Man; the magical activation of stone circles’ ancient defence

mechanisms in The Mind Beyond episode ‘Stones’; and the ‘Albion in the

overgrowth’ recalibrating of mainstream television in McKenzie Crook’s Worzel

Gummidge.

A YEAR

IN THE COUNTRY

CATHODE

RAY AND CELLULOID HINTERLANDS

The

Rural Dreamscapes, Reimagined Mythical Folklore and Shadowed Undergrowth of

Film and Television

Published

by: A Year In The Country, 2022

All

rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise) without permission from the publishers.

www.ayearinthecountry.co.uk

ISBN:

978-1-9160952-5-0

Copyright

© Stephen Prince, 2022

Edited

by Suzy Prince

Cover

image and typesetting by A Year In The Country / Stephen Prince

Other

books by Stephen Prince:

A Year

In The Country: The Marks Upon The Land

A Year

In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields

A Year

In The Country: Straying From The Pathways

The

Corner Mother

The

Shildam Hall Tapes

Albums

by Stephen Prince:

The Corn

Mother: Night Wraiths

The

Shildam Hall Tapes: The Falling Reverse

Albums

by Stephen Prince (working as A Year In The Country):

Airwaves:

Songs From The Sentinels

No More

Unto Dance

Undercurrents

Contents:

Introduction

– 9

Notes on

the Text – 20

Preface:

A Definition of Hauntology, its Recurring Themes and Intertwining with Otherly

Folk and the Creation of a Rural and Urban Wyrd Cultural Landscape – 21

1. The

Wicker Man: Casting Aside Convention on Summerisle – 28

2. Paul

Wright’s Arcadia: Views from a Not Always Arcadian Idyll – 48

3.

Excalibur: John Boorman’s Creation of an Otherwordly Arthurian Dream – 55

4. Play

for Today and Rainy Day Women: Village Mob Rule and the Spectres of Archivel

Television – 73

5.

Bagpuss: Portal Views Into a Magical Never-Never Land – 82

6. Takashi

Doscher’s Still: Explorations of Southern Gothic, Wyrd Americana and Eternal

Cycles – 90

7. Gone

to Earth, The Wild Heart and Talking Pictures TV: Stories from the Haunted

Borderlands, Conflicts Between the Old Ways and the New and Preserving the Fading

Shadows of Film and Television History – 103

8.

Strange Invaders, Robert Fuest’s Wuthering Heights, Kate Bush, Oklahoma Crude

and Twilight Time: A Time Warp Small Town Invasion, Passion Amongst a Downbeat

Landscape, Untamed Frontiers and a Media Sunset - 121

9. The

Mind Beyond and ‘Stones’: Activating Ancient Pretenatural Defence Mechanisms

and a Sidestep into the Pioneering Work of Irene Shubik, Verity Lambert and

Delia Derbyshire – 134

10. Oss

Oss Wee Oss: Joining the Dance Far Away from the City – 150

11. The

Straight Story: Road Movie Quests and a Gently Lynchian View of Journeying

Through a Near Mythical Landscape – 162

12.

Shadows: The Layering of Time, Folklore and Myth – 173

13.

Codename Icarus: Teatime Cold War Intrigues Hidden Amongst the Bucolia – 191

14. The

Creeping Garden: The Slipstream Explorations of a Science/Science Fiction

Fantasia – 207

15. E4’s

‘Wicker Man’ Ident: An Edge of the Field View of a World Unto Itself – 214

16.

Raven: Unearthing Hidden Buried Power and Battles to Safeguard the Future – 219

17. –

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker: Seeking Answers in the Forbidden Zone – 231

18.

Radio On and Fords on Water: Escape and Exploring the State of the Nation in

British Road Movies – 257

19.

Whistle Down the Wind: Adventures in a Time Capsule Landscape – 273

20. Hell

Drivers and The Bargee: Searching for Freedom and Autonomy in an Overlooked

Corner of the Landscape and During the End of an Era – 284

21.

Stargazy on Zummerdown: Starships, Pedlars and Morris Dancers Meet in Utopia -

289

22.

Robin and Marian: The Return and Reimagining of a Living Legend – 313

23. The

Nightmare Man: Frankenstein-Like Meddling Away from the Mainland – 319

24.

Worzel Gummidge: MacKenzie Crook’s ‘Albion in the Overgrowth’ Recalibrating of

Mainstream Family Television – 326

Appendix:

The ‘Good Housekeeping’ Wiping Television Archives – 339

Introduction

The word

‘hinterland’ in this book’s title refers to the term’s meaning and use to

describe an area that lies beyond what is visible or known, and this in turn

connects with the three main interwoven strands and characteristics of film and

television which are referred to in the book’s subtitle and that are the

central themes of the book:

1. Rural

dreamscapes: the depiction of rural areas where normality, reality and

conventions fall away and/or are able to be sidestepped, and of the landscape

as being deeply imbued with hidden, layered and at times dreamlike or

otherworldly stories.

2.

Reimagined mythical folklore: the differing ways that traditional myth and

folklore have been explored, reimagined and reinterpreted.

3. The

shadowed undergrowth of film and television: work which is semi-obscured from

view through one or more of a number of factors such as no complete versions

being known to still exist, having had only a very limited cinema release, no

longer being available to officially easily view at home due to DVDs etc. going

out of print and becoming rare and/or high in price and/or never having been

officially released digitally, work that since its initial broadcast decades

ago has only been available via unofficially distributed degraded quality

versions and so on.

The book

is released as part of the A Year In The Country project which has a broad

reach, but at its core is an exploration of what could be called ‘otherly

pastoral’ or ‘wyrd’ culture, that incorporates the undercurrents and further

reaches of rural and folk-orientated music and culture, and where these meet

and intertwine with what has come to be known as hauntology, which is a loosely

interconnected area of culture that is part characterized by its creation of

parallel worlds which contain reimagined spectral echoes of the past and a

yearning for lost progressive futures.1

A Year

In The Country began in 2014, and as part of the project since then there have

been more than 30 book and music releases alongside over 1,100 posts on the

website which (among other things) consist of artwork and written pieces

inspired by, and relating to, that otherly pastoral/spectral hauntological

intertwining.

Along

the way the project has explored and connected multilayered and often hidden

pathways and signposts that have sometimes become buried inn the cultural

undergrowth over time: from explorations of the eerie landscape to tales of

hidden histories via the shape of the future’s past that can be found in

Brutalist architecture, alongside acid and underground folk, ‘edgelands’,

electronic music innovators, older British public information films, rural

progressive or utopian settlements and associated temporary autonomous zones

and photographic countercultural festival archives, early canonic and modern

folk horror film and television work, the unsettled times and atmospheres of

the Cold War, folkloric film and photography, the faded modernity and future

ruins of road travel, imaginary film soundtracks, the ‘ghosts’ and forgotten

far-reaching projects of the former Soviet Union, contemporary

hauntological-esque music releases and hazily misremembered televisual tales

and transmissions and an accompanying strand of later 1960s through to early

1980s young adult-orientated British television series which had surprisingly

complex and/or dark themes.

On the A

Year In The Country website and in the books published as part of the project

the resulting work has included writing on the likes of, amongst many others:

the films and television programmes The Owl Service (1969-1970), The Changes

(1975), Children of the Stones (1977), Nigel Kneale’s work such as The Stone

Tape (1973) and Quatermass (1979), Bagpuss (1974), The Moon and the

Sledgehammer (1971), The Wicker Man (1973) and Kill List (2011); music by the

BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Howlround, Vashti Bunyan, Anne Briggs, Jane Weaver

and Kate Bush and released by the labels Folklore Tapes, Trunk Records and

Ghost Box Records; and the photography books Memory of a Free Festival (2017),

Homer Sykes’ Once a Year: Some Traditional British Customs (1977), Sarah

Hannant’s Mummers, Maypoles and Milkmaids: A Journey Through the English Ritual

Year (2011) and Rebecca Litchfield’s Soviet Ghosts (2014).

The

albums released by A Year In The Country have included a number of themed

compilations that, via work created specifically for them, explored

interconnected areas of culture, history and memory, including (again amongst

others): abandoned villages, the flashpoints of history and conflict in the

landscape, derelict Cold War infrastructure, ancient trees and their passage

through time, the faded dreams of the space race, deserted industry and echoes

of tales from woodland folklore. Alongside work by myself, they have featured

contributions by, alongside other contributors: Pulselovers, Sproatly Smith,

The Séance, Widow’s Weeds, The Heartwood Institute, Depatterning, Howlround,

Field Lines Cartographer, Dom Cooper, Keith Seatman, Grey Frequency, Time

Attendant, The Rowan Amber Mill, Listening Center and Vic Mars.

I have

written about some of the roots and inspiration for A Year In The Country in

previous books released as part of the project and on its website, but in order

to provide a background for this book, and also as some reading it will not

have read the earlier work, I discuss and at times revisit some of the

inspirations and pathways that lead to A Year In The Country below.

In part

the roots of A Year In The Country probably stretch back to decades before it

began, when at a young age for a while I lived in a small rural village and

spent much of my time living a bucolic existence bike riding, climbing hills,

damming rivers and so forth. But at the same time, this was to a background of

becoming aware of the threats, worries and paranoia of the Cold War and also

discovering exploratory, dystopic and catastrophic science fiction in books and

television that while thoroughly intriguing me may also in part have been a

little too old for me to fully understand and/or that had at times decidedly

unsettling themes and atmospheres. These included intriguing glimpses of the

dystopic young adult orientated television drama series Noah’s Castle (1979),

which I did not see in full at the time but saw just enough of for its

depiction of societal collapse and hyperinflation lo linger in an intriguingly

unexplained and half-known way in my imagination. Around a similar time, I also

saw and read the aforementioned final 1979 series and the accompanying

novelization of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass and their stories of the extraterrestrial

harvesting of the world’s youth amongst ancient rural stone circles, John

Wyndham’s post-apocalyptic Day of the Triffids (1951) and its terrifying-at-times

1981 television adaptation and also Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos (1957), in

which a village is invaded by a preternatural hive mind group of children. The

latter of these I never knew the ending to until many years later, as the copy

I read had the last page or so missing and so I did not know if the village was

saved or not.

I state

in A Year In The Country: Wandering Through Spectral Fields (2018):

“This

mixture of a pastoral playground, a world on the edge and fantastic fictions

proved to be a heady mix for the dreamscapes of a young mind, all of which

would be some of the initial seedlings [that] would lead one day to the

creation and ongoing themes of A Year In The Country.”

If I

look back to before my time living in that village, my interest in rural areas

begin depicted in fictional work as containing a sense of being ‘otherly’ or

‘wyrd’, alongside an accompanying and intertwined interest in hidden half-known

stories, may also have some of its roots in a time when one of my teachers

would only read the first few chapters of a book to the class I was in, hoping

that it would encourage her pupils to read more, wanting to know how the

stories ended.

One of

these books, which I did not subsequentlty finish reading myself, has stayed

lodged in my imagination ever since, although I still do not know the name of

it and I am not sure if I want to as I seem to prefer it existing in a

half-known state in my mind. All I can remember is it being set rurally and a

few hazily recalled characters and plot points, which included a benign

witch-like older woman with knowledge of the ‘old ways’ and it featuring some

form of ancient stone with possibly less benign mystical qualities which she

guides two children, or possibly teenagers, to neutralize in a both magical and

prosaic seeming manner.

The way

that this story remained part known, open-ended and a thing of mystery,

alongside only seeing glimpses of Noah’s Castle and not knowing the ending of

The Midwich Cuckoos are part of what semi-consciously inspired the “shadowed

undergrowth” theme of this book.

In more

recent times, several years before I started A Year In The Country, I listened

to a friend’s copy of the compilation album Gather in the Mushrooms: The

British Acid Folk Underground 1968-1974, which was released in 2004 and curated

by Bob Stanley of Saint Etienne. The reimagining and pushing back of the

boundaries of folk music on the album seemed to open up something in my mind,

and this was a notable influence on the creation and themes of A Year In The

Country.

Around

the same time and in the period that followed hearing that album I listened to

The Advisory Circle track ‘And The Cuckoo Comes’ from the Mind How Go album

that was originally released in 2005 by the aforementioned Ghost Box Records: a

label that explores a hauntological-esque parallel world, and I also watched

the videos which accompanied the album by Broadcast and The Focus Group:

Investigate Witch Cults of the Radio Age (2009), which featured collaborative

work between Broadcast and Julian House, the latter of whom is one of Ghost Box

Records’ founders. This track and the videos have a woozy, hazy dreamlike and

at times unsettling rural atmosphere, and in the case of the videos also

implies that the rural areas they take place in contain hidden, unexplained and

layered stories.

Accompanying

this, around a similar period I read Allan Brown’s book Inside The Wicker Man

(2000), which in part explored the also hidden and layered stories around the

now-iconic 1973 folk horror film The Wicker Mans’ production, and I also

semi-consciously became intrigued by the 1998 red vinyl edition of the film’s

soundtrack released by Trunk Records. The latter of these contained a location

map from the film, which through its hand-drawn and photocopy-like character

seemed to imply that you were looking at something only semi-known or an

unearthed secret.

The

Wicker Man became one of the recurring touchstones and reference points for A

Year In The Country, as did the sense of no complete version of it still being

known to exist and how watching it can be like being given an extended glimpse

of the ghost of the full film. Viewing it can also be not dissimilar to

watching an almost fever dream-like documentary about the way of life and

events on its isolated island location, and it creates and depicts a world unto

itself where wider societal norms and conventions have been cast aside.

Alongside which its story and world are deeply imbued with myth and folklore

that seems to draw from, refract and reimagine traditional folk culture and

ancient stories, rituals and beliefs, and to connect with hazily distant

half-known memories of them.

The

sense of reimagining mythology, folklore and folk culture and the landscape

being layered with dreamlike, semihidden stories and secrets in work such as

that referred to above, alongside a loosely interconnected landscape of other

work that explores interrelated areas, and my discovering and investigating it

combined and intertwined to become part of the inspiration for the themes,

atmospheres and explorations of A Year In The Country and subsequently the

three central themes of this book.

As

referred to previously, part of the “shadowed undergrowth”, semi-obscured or

semi-hidden aspect of those themes refers to the way in which there is a large

subsection of film and television that is lost or obscured in plain sight, at

times perhaps forever, which includes the just mentioned complete version of

The Wicker Man.

Despite

the vast range of older film and television productions that have been released

as DVDs, Blu-rays and/or digitally, there are still large gaps in what is

available to view at home, or at least view more easily, in reasonable quality

and/or officially. Sometimes this is because, in part, as mentioned previously,

official physical releases may be out of print and have become scarce or

relatively expensive to buy or were only released via now obsolete formats,

films and programmes never having been officially released in any for for home

viewing after their initial cinema release/television broadcast, them only ever

having been released on Blu-ray and/or DVD that are ‘locked’ for viewing in

particular areas of the globe, them only having been distributed unofficially

online in degraded quality form etc., or in the case of The Wicker Man it is

because the complete version or the ability to recreate it is probably not

possible due to the footage being Thought to have been disposed of, some

versions of the film becoming lost and so on.2

Also, the

gaps in what is available to view easily, officially and/or at all is partly

due to how in previous decades television programmes were not always archived;

this was for a number of reasons: sometimes they were performed and broadcast

live and not recorded or often the recordings, or at least parts of series,

were later wiped in order that tapes could be reused both because their

relatively large physical size meant that they required a large amount of

storage space which in turn resulted in archiving them being costly and also

the high cost at the time of such recordable media meant that being able to

reuse it could cut production cists. Alongside this was not always realized

that programmes would be of interest in future years, possibly in part because

in previous decades ‘repeats’ of programmes were seen as something to complaint

about.3

Accompanying

these factors a number of television and film programmes from previous decades

do still exist but are only available for official viewing at particular

locations via private viewings, as is the case with a number of British films

and programmes that are stored at the BFI National Archive.

Curiously

some of the ‘obscured from view’ television programmes that have never had

official home releases in any format since their initial broadcasts, including

some ‘wyrd’ rural culture-related ones that are discussed in this book, do

surface online, often uploaded unofficially by, presumably, the general public

to high profile open-access video streaming sites such as YouTube, but it is

not always clear what the origin of the videos are. They may be from television

broadcasts that were recorded by the public on home video cassette recorders

and later digitized, but some contain timecodes or studio countdown intro

sequences, which imply that at some point they were copied from master tapes

and/or internal production copies.

These

unofficially distributed versions are often, if not generally, poor quality and

it is quite likely that they are multi-generational copies; watching them can

be akin to viewing an impressionistic interpretation of the original

recordings, where the world as depicted in them, the stories they tell and the

atmospheres they create are murky, smeared and seen through a haze of degraded

media. Because of this they are a distinctive and curious anomaly in the

current media landscape where films etc. are often released for home viewing in

ever-higher resolution and once prepared for release utilise the

generally-precise replication processes of digital distribution. Also, at the

same time, the low quality of such unofficially distributed versions of

programmes etc. becomes almost an inherent part of their character and lends to

them a sense of being hauntological spectral versions of themselves.

Although,

as referred to above, these are not officially sanctioned releases, the copyright

holders seem to not know of or overlook them, or at least they do not appear to

rigorously seek them being removed. Perhaps they do not have the resources to

do this, or do not focus on preventing the unauthorised distribution of these

sometimes semi-forgotten programmes but rather direct their attention and

resources toards controlling the unauthorised distribution of higher profile

and more indemand content. Whatever the reason, this overlooking could be

considered to make their distribution not so much a form of forbidden

samizdat-like publication but rather a form of archival folk preserving and

distribution of culture that, while unsanctioned, acts as a substitute for

official releases.

This

book focuses in part on such unofficially distributed television programmes,

including Stargazy on Zummerdown (1978), Rainy Day Women (1984) and The Mind

Beyond episode ‘Stones’ (1976) but I am

aware that by the time it is published and read some of the programmes which

are written about may have become officially available or some may no longer be

‘unofficially’ available. Alongside which, some of the films and television

programmes discussed in the book that at the time of writing were not always as

easily available for home viewing due to one or more of the previously

mentioned factors such as DVDs going out of print and becoming rare, high in

price etc., may have been reissued in one form or another in the UK and/or

elsewhere. With this in mind, the book is a snapshot of a particular point in

cultural time and place and also of the spectral ‘lost in plain sight’

character of these films and television programmes.

In part,

the book reflects and documents a form of personal detective story during which

trying to discover, for example, what official versions have been released of

certain films and television programmes, if any, and in what forms, countries

etc.; if unofficially distributed programmes etc. are available for official

viewing in archival collections; if a programme was only broadcast once;

tracking down writing that is long out of print and/or has never been put

online which focused on a particular film or programme that had also not been

written about extensively and so on became a type of intriguing and engrossing

puzzle.

Accompanying

which, it may be the semi-hidden nature of such film and television programmes

and the work required in seeking out and connecting information about them that

is an element of what drew me to them, particularly due to it contrasting with

the wider contemporary cultural landscape where much of culture is easily

available via the click of a mouse, tap of a remote etc.

Interconnecting

with this, and to a degree also contrasting with it, the book does not overly

focus on licensing, copyright ownership issues etc. which may have resulted in

films and television programmes not being available. Rather it approaches their

release (or non-release etc.) from a standpoint that, in these days of potential

ease of cultural distribution and access via digital networks, it is interesting

and curious that there is still often a notably piecemeal and patchwork

availability of much of film and television, whether in terms of it being

officially available at all, which countries it has been released in, the

varying costs of releases, what platforms and/or formats it is available on

etc. Such aspects of film and television distribution seem to be distinctively

disparate to the contemporary digital release and distribution of music, which

is, generally much more internationally standardized and widely available

across a variety of platforms. This disparity remains notable even with an

awareness that the film and television-related copyright and licensing issues,

production costs, the creation of digital transfers etc. are potentially more

expensive and complicated than with music.

With

this in mind, to a degree, the book has something of an underlying, and until

had finished it probably largely unconscious, theme of being intrigued and

surprised that the distribution and ease of access to film, television etc.,

has not ‘settled down’ into a largely more standardized widespread

digitally-available model as has occurred with music.4

The

Wicker Man contains and reflects many of the central themes of the book

through, as discussed above, its depiction of an isolated rural world unto

itself where normality and conventions have fallen away, its refracting of

traditional myth and folklore and there being no complete version of it being

known to still exist. Also much of contemporary ‘otherly pastoral’ or ‘wyrd’

rural culture and the flowering of interest in such things, including my own,

has been inspired by and flows from the film, and because of these various

characteristics and factors the chapter which focuses on The Wicker Man ids the

first in the book.

I hope

you enjoy the ‘wanderings’ through rural dreamscapes, reimagined mythical

folklore and the shadowed undergrowth of film and television in this book, and

that it helps to inspire explorations and journeys through your own cathode ray

and celluloid hinterlands.

Stephen

Prince (19th July 2021)

1.

Hauntology, otherly pastoral and wyrd culture are discussed further in the

Preface.

2. I

discuss related themes with regards to The Wicker Man in Chapter 1.

3. The

background to such ‘wiping’ practices and related themes are discussed further

in the Appendix.

4.

Related themes are discussed further in Chapter 4.

_Bubok.jpg)